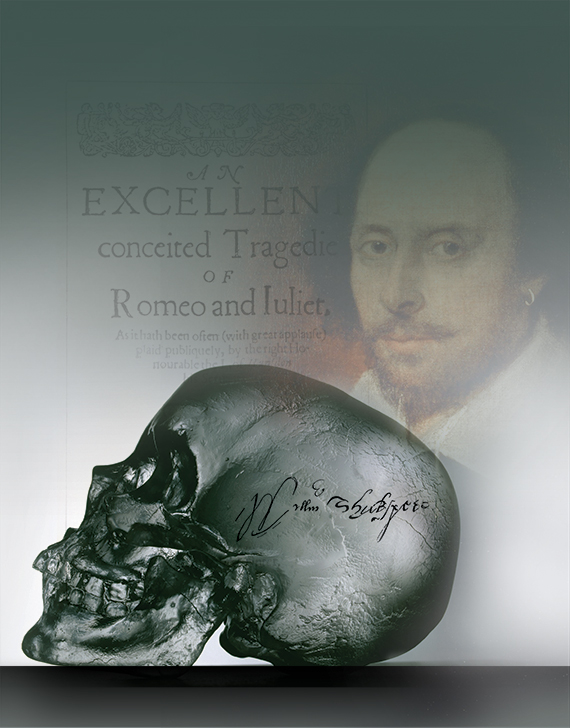

What better way to remember Shakespeare, arguably the UK’s best-known literary land owner, than by investigating the commercial relationship between property and theatres 400 years after his death?

Culture and economy, passion and reality, creativity and pragmatism. When it comes to valuing theatres and their complex relationship with developers, it is all about balance. The big question is how can the equilibrium be addressed, perfected and maintained?

It helps if both parties are looking to work more effectively together. Good news, then, that in the 400 years since the death of William Shakespeare – himself a savvy land and property owner – the relationship between the two looks to be reaping significant commercial benefits.

It helps if both parties are looking to work more effectively together. Good news, then, that in the 400 years since the death of William Shakespeare – himself a savvy land and property owner – the relationship between the two looks to be reaping significant commercial benefits.

“Can we find a viable economic case for investing in theatres?” asks Melanie Leech, chief executive of the British Property Federation. “Hard-nosed developers think the answer is yes.”

The phrase “hard-nosed” is the operative one here. A fresh, new focus on performing arts spaces − restoring and saving historic ones as well as including modern sites as

part of new developments −

is being led by some of property’s biggest names: Shaftesbury, Berkeley Homes and Land Securities, to mention a few.

And in a world where even the most culturally sympathetic property developer has to be able to see the economic validity of any project, it appears that the sector sees theatres and the wider performing arts sector as a bona fide investment case.

That’s not to say there are not still challenges to overcome. Planning, valuation, prioritisation and budget cuts all still remain very real hurdles. So how are the theatre and property worlds working together to surmount these issues? And what sort of returns are being delivered as a result?

Working together

When it comes to whether developers and theatre owners can work together to find new models to create social, cultural and economic return, Shaftesbury Estates is the ultimate case in point.

The London-based developer known for its vast West End portfolio does not actually own any of the theatres which sit on its land bank. And yet they remain crucial to the success of the estate.

“Our curated portfolio of shops, restaurants and bars celebrates the rich experience of visiting the West End of London,” says Julia Wilkinson, portfolio and strategy director at Shaftesbury. “So it is no coincidence that Theatreland lies at the heart of our holdings, which reflect the economic strength of theatres and their ability to attract visitors to the West End.”

But it is not just existing stock that can deliver value. New developments centred on theatrical elements are becoming increasingly popular.

Berkeley Group’s new 88-acre Woolwich Arsenal development is a case in point, where 20% of the space will be dedicated to culture. At the heart of the scheme will be a performing arts centre, which will play host to the world-famous Hofesh Shechter contemporary dance company.

And The Stage, Cain Hoy and Galliard’s £750m scheme in Shoreditch due for completion in 2019, is not only being built on the site of the Elizabethan Curtain Theatre, but will be centred on the excavated ruins of the old performance space.

On London’s South Bank, home of Shakespeare’s original Globe and Swan Theatres, former National Theatre top brass Sir Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr are raising the curtain on a new 900-seat auditorium for their London Theatre Company, following a deal with Berkeley Homes at One Tower Bridge, SE1, due to open in spring 2017.

“We took no persuading,” says Starr. “We had already figured out that we couldn’t compete on rents with other occupier classes elsewhere.”

He had done his research, which included talking to fellow theatrical enthusiast Robert Wolstenholme, managing director at Trilogy Property. “We were both on the board of the Bush Theatre in West London. We talked, and he took me to the Tower Bridge site,” he says. “Then Nick came and visited the next day. We both turned up thinking it wouldn’t be of any interest but we were completely blown away by the space. There it was – who knew? – a huge aircraft hangar sunk into the banks of the Thames.”

The wide, thrust-stage theatre will open in summer 2017, and the rent on the 45,000 sq ft space is the subject of some un-theatrical discretion: “We’re paying a commercial rent, and we’ve got a long lease,” says Starr. “Berkeley turned down other potential tenants for us, a start-up.”

Harry Lewis, managing director of Berkeley Homes (South East London), could not be happier. A large space is off his hands – and the reputational gain is huge. “The theatre will help establish this area as the Covent Garden of the South Bank,” he says. “We’ve already signed up The Ivy to operate an 8,000 sq ft restaurant and we have other high-quality retailers coming.”

Alas, the theatre was poorly timed to lift sale prices at the schemes’ 419 flats. “Ninety-five per cent were already sold, so the theatre came a bit late in the day to boost values,” says Lewis.

To the regions

And the positive relationships are by no means restricted to London. Since May last year HOME, an arts centre with two theatres (one of 500 seats and another, more flexible, of 150 seats) in Manchester has sat at the heart of Ask Development’s (and now Patrizia’s) 20-acre First Street office, residential and leisure scheme.

Also in Manchester, Allied London’s £1.4bn St John’s redevelopment will include the Rem Koolhaas-designed The Factory − a complex of performance spaces backed by £78m from the government and due to open in 2019. Katie Popperwell, Allied London’s cultural director for the new quarter, says the key to success will be getting The Factory to work well with other parts of the project. “It is about sensitive programming,” she says. “At the moment this is about concepts, not bricks and mortar, so we are trialling projects that might work.”

The evidence suggests that the time is ripe for developers and theatres to work together. As long as those all-important returns can be secured: “Theatres have long been a compelling part of our towns and cities,” says the BPF’s Leech. “And when they are used effectively they can significantly add value to the offering in that location.

“Developers are seeing the opportunities of building theatres and public performing spaces… critical to their success is finding a viable economic use for the building itself which supports refurbishment, generates income and secures the long-term maintenance and future of the building… The economic case is just as important as the artistic one because otherwise you are pouring money into an unsustainable black hole.”

But how do you ascertain value when it comes to theatres?

Theatrical values

“I think it is difficult,” says Phil Holden, assistant director at Deloitte Real Estate. “There is no ‘one size fits all’. There are different valuation methods which will depend on the type of property, what the use is, the breadth of the market for that particular building.”

Theatres are valued as individual trade-related properties where, essentially, the valuation is based on the trading potential of each building. From the condition of the fixtures and fittings to the state of the bars on site, theatres are traded based on a valuation of the potential to generate operating profit.

This comes down to a balancing of the state of the bricks-and-mortar side of the theatre with the financial output.

Ollie Saunders, lead director of alternatives at JLL explains that, like any valuation, the ultimate figure is based on comparing and contrasting the property to the rest of the market. And depreciated replacement costs are used when there is no existing market to use as a benchmark for a comparison to ascertain the value. So you work out what it would cost you to buy and rebuild that theatre today. Not five, 10 or 15 years ago, but today, to replicate the market’s ‘likely judgment’.

“We look at three factors,” says Saunders. “First, physical. How knackered is the building? Is the roof leaking? Then it’s the functional factors. Can you get customers into the bars? Can you actually fit music productions onto the stage to drive revenues? And then external obsolescence − are theatre numbers falling? Is there an economic crisis? Is there a lack of creative output from the producers?”

The valuer will then work up the cost of a top-performing theatre and would use that as a benchmark from which to deduct value based on how well the theatre compares on the criteria set out above.

Improving mood

So if the venue is there, it can be quantified. And the plethora of schemes – old and new – where there is a focus on performing arts suggests that value can indeed be found.

But relationships between performing arts and property haven’t always been so cordial. The Theatres Trust was set up in 1976 to protect London’s older, gilded theatres from redevelopment and 40 years on the mood is much improved – but not entirely.

Trust director Mhora Samuel was recently forced to leap to the defence of London’s Victorian theatres after Nick Starr declared them more-or-less redundant for contemporary productions.

But ultimately the trajectory has been a positive one. “We were set up because so many West End theatres were being bought and demolished, or demolition was planned,” says Samuel. “Today it is rare to find an existing theatre threatened by a developer. They either replace, or retain and enhance.”

The trust polices the system as a statutory planning consultee, inspecting 120 planning applications and 60 listed buildings applications each year. “We’re not seeing the same level of threats to theatres because theatre is stronger than it has ever been. But we also have stronger policies to protect theatres in local planning documents,” she says.

But threats do still exist – the Trust maintains a list of 31 theatres at risk. The Brighton Hippodrome is moving off the list now that a local community group has bought it, while Manchester’s historic Theatre Royal is almost a permanent fixture. Having survived a 2008 plan to replace it with Benmore’s 30-storey Intercontinental Tower (complete with helipad), it was acquired in 2012 by the Edwardian Group. Silence has since descended, perhaps connected with the city’s long-term aim of attracting the Royal Opera House to Manchester. A theatre said to have inspired the design of its Bow Street, WC2, premises, could hardly be more appropriate.

Verifying value

Reaching an equilibrium is hard. Maintaining one is tougher. And on the subject of valuing theatres, the balance between maintaining decent bricks and mortar and delivering returns is a tough one to keep on an even keel.

But where there is adversity, innovation often follows. And that innovation needs to come from the cultural, as well as the commercial, side of the relationship. The appetite from developers is there, so long as theatres are willing to prove their worth. And when it comes to the crunch, that’s the valuation that really matters.

New London theatres

The Theatres Trust says as many as 15 theatre schemes are in the pipeline. These include Soho Estates’ 120-seat Boulevard Theatre at Walkers Court, W1, due for completion in 2018. In Wembley, north-west London, Harvey Goldsmith has commissioned a rotating auditorium (instead of changing scenery, the audience is moved to a new set), a new studio theatre is appearing in Peckham, SE15, and on Tottenham Court Road, WC1, Nimax plans a new theatre as part of the Crossrail development.

Will’s way with property

William Shakespeare was a frequent buyer and seller of real estate. Not just theatres, but slices of well-located London land and tracts of Warwickshire farmland. He bought 107 acres in Warwickshire in 1602, the first of several purchases, and in 1613 he paid £140 for Blackfriars Gatehouse, his first London property, possibly as a city pied-à-terre. The site is thought to be somewhere between St Andrews Hill and Wardrobe Place, perhaps on the north side of Ireland Yard, EC4.

Let’s do the show right here

Who needs theatres when you can perform anywhere? Site-specific or found spaces are the super-cool pop-up choice of many of today’s producers and directors. For the owners of the newly found spaces this helps animate otherwise empty buildings and create funky new branding.

Central Saint Martins moved to a new campus in King’s Cross, N1, in 2011, leaving its former home at 111 Charing Cross Road, WC2, empty. In 2012 it was acquired by Soho Estates in 2012 as part of the acquisition of the Foyles Soho portfolio. The building is now a theatre hub, with Found111 using 9,000 sq ft on the third and fourth floors as a pop-up theatre, while secrecy-obsessed immersive theatre group You Me Bum Bum Train has 7,800 sq ft on the first and second floors in space is donated by Soho Estates.

It sounds new, but of course it isn’t. In Shakespeare’s day, theatre was rarely performed in purpose-built buildings – there were only a handful in existence, all in London. Instead, performers had a give-and-take relationship with landlords. The most popular locations were inn yards (because it helped drive ale sales), private houses and official venues (because it was very swanky), and anywhere you could wheel a cart-for-a-stage (because it was free).

• To send feedback, e-mail emily.wright@estatesgazette.com or tweet @EmilyW_9 or @estatesgazette