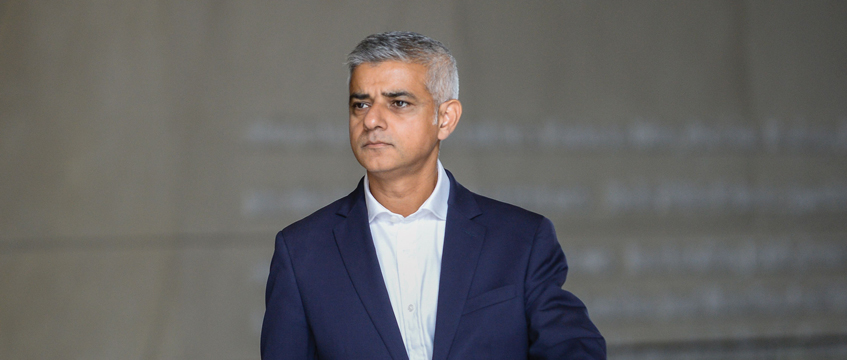

After five years at City Hall, London mayor Sadiq Khan remains largely a stranger to the development industry. Although his stringent housing policy has seen a rise in affordable homes, it has also deterred development, with many avoiding the capital and those companies that are active in London often kept at arm’s length.

Following Khan’s fresh victory at the polls, industry figures are now calling for greater collaboration in planning, development and financing for housing.

“What developers want is a little bit of certainty,” says John Walker, former Westminster planning director and executive director at CT Local. “They need a little bit of a steer when it comes to acquiring sites and investing. They haven’t got that at the moment, and that is why so many investors have stopped investing in London.”

Walker says meetings with top decision-makers in planning are essential so that developers know whether to pursue schemes. Liz Peace, former chief executive of the British Property Federation and chair of the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation, adds that this is needed to overcome a disconnect between some London boroughs and the Greater London Authority.

“Developers are left with a fair degree of uncertainty about who to talk to,” says Peace. “Even if they talk to somebody, is it going to get overturned? We really need some sort of serious clarity.”

In the absence of direct interaction with the mayor, many industry players have learnt to work with deputy mayors, says Jonathan Seager, executive director for policy at London First. But that still leaves “a bigger issue at play”, Seager adds, noting that the mayor’s housing ambitions are constrained by a lack of resources: “The amount of money that the mayor has is nowhere near where we actually need it to be.”

Priced out

The affordable housing programme offers £4bn nationwide over five years, whereas London First estimates that London needs £5bn per annum to deliver the affordable homes the city needs.

“London has an affordability problem, and the mayor wants to set some very stringent criteria to try and address that,” adds Peace. By forcing developers to foot the bill, development in London is made unviable, but with lack of subsidy there is no alternative. “How are you going to square that circle?” asks Peace. “Developers can’t do everything, which is why you’ve got to get really creative and start to try and find ways of unlocking new models.”

One such idea is exploring land supply and the cost of land. Peace says this means “finding the right land, in the right scale, with the right assembly”. This opportunity struck Peace through her work with the Homes for Londoners board. “There could be more co-ordination to identify sites and then go on to leverage investment,” she adds.

Walker argues that local authorities should be responsible for delivering affordable homes and strategic site assembly, led by targets from the mayor. This would streamline planning for developers and see the state look after state-funded affordable homes.

“We need to do more on CPO,” says Walker. “Let’s not forget that the public sector can borrow money at better rates than the private sector.” This, combined with grant finance, can fund upfront infrastructure. “I don’t see enough of that taking place,” he adds.

Nonetheless, a shrinking supply of public finance and uncertainty around a new developer levy for affordable homes could be a real challenge. In lieu of this, new ideas are emerging to bring private investment alongside public funds.

Mingling with the mayor

A year ago, Khan gave the green light to begin market testing new opportunities to expand the London Land Fund. The current fund combines £250m from the GLA with £486m in government funding, but is unable to meet demand for projects.

London First and PwC estimate that by including private sector investment this could grow to £1bn, with a capacity for 20,000 homes over a decade. “It’s all about additionality,” says Seager. “There are lots of brownfield sites in London, but many of them are in challenging circumstances.” Many sites need remediation, have complex ownership structures or require infrastructure investment.

Seager says extending the fund can tackle this, noting that City Hall has the skills and capacity to provide support. He adds: “It’s not just about private investment. You can work with local authorities, pension funds – there’s a whole range of stakeholders that could be brought into this.”

This approach should not be limited to just the land fund. Seager adds that as the private sector heaps funding into affordable housing via registered providers and housing association deals, the mayor’s office can support this investment.

“Sometimes these are politically difficult to agree, but you can either stand on the sidelines and watch this happen or you can actively get involved – you can shape and harness it,” says Seager. “There is huge potential for the mayor to bring forward some kind of vehicle which, working in concert with local authorities, could actually start to really attract private investment.”

Peace adds: “Confront affordable housing head on. Find vehicles or create vehicles, rather than trying to sneak it in by the back door. See this as a proper asset class into which you can encourage real investment.”

LISTEN: Resi Talks: Housing challenges for London’s next mayor

To send feedback, e-mail emma.rosser@egi.co.uk or tweet @EmmaARosser or @estatesgazette