By the end of 2016, women could be in charge of three of the largest economies. What would this mean for the world? And could it get us to the point where women taking charge is finally not noteworthy? Janie Manzoori-Stamford reports

Who runs the world? Well, quite frankly, who knows anymore? With governments in turmoil and a plethora of elections set for the next two years in America, France, Austria and Germany to name a few, the line-up of global head honchos is changing fast. And often. But there is one clear pattern emerging: the rise of the female superpower squad.

Theresa May, Angela Merkel, Hillary Clinton. Come November we could see three of the world’s largest economies run by women for the first time in history.

Last week Estates Gazette interviewed Grainger’s leadership team – the first all-female chief executive, chair and financial director trio in UK property (16 July, p44). Appointed not because they are women, but because they are simply the best qualified for the jobs, it marks a sea change in the industry. One that many hope will send waves through the sector and push the equality debate on in leaps and bounds. So could this happen on a bigger, global scale? From world leader status down?

Property is by no means unique in its gender imbalance. The female of the species typically plays second fiddle in politics too. Less than 5% of world government leaders are women. But recent events and a forthcoming election suggest that we could be on the cusp of a revolution.

Apart from being a positive step for gender equality, what would it actually mean for the world if women were at the top of three of our biggest global economies? What influence could such a trifecta have on business? Could it change opinions and help to further push for equality and diversity across the board? Will it be the leap we need to not only move chatter away from the new PM’s choice of kitten-heeled footwear, but also get us to a position of equality that would render this whole debate entirely, finally and happily defunct?

The glass cliff

“Fascinating and unprecedented.” This is one take on the possibility of a May/Merkel/Clinton future from Elin Hurvenes, founder and chief executive of Professional Boards Forum, an organisation set up to help Norwegian companies increase the number of women on corporate boards from 6% to 40%. She says: “The big question is, will we see new and different ways of communicating; of solving conflicts and issues?”

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF, certainly thinks so. She is a firm believer in the theory that women are better at coping than men in troubled and uncertain times. Asked by Inc.com in 2013 whether women make better leaders than their male counterparts, she said: “In a crisis, yes,” and cited Iceland as an example. “The country essentially went down the tubes. Who was elected prime minister? A woman. Who was called in to restore the situation with the banks? Women. The only financial institution that survived the crisis was led by a woman,” she said.

How much weight does that claim hold? According to Michelle Ryan and Alex Haslam, psychology professors at the University of Exeter, it is certainly the case that women are more likely to be put into leadership roles under risky or precarious circumstances, a phenomenon they have dubbed “the glass cliff”.

But sometimes it is much simpler than that – tough gigs are easier to win because the competition drops away.

“In business, women don’t often get asked to take on a chief executive role, and when they are, it is often of companies in deep crisis, where men have already turned the offer down because they think it’s a kamikaze mission,” says Hurvenes. “Women sometimes accept this position because they reckon it’s their only shot.”

This might be the case, but that is not to say women fail to perform when they reach the top, even in hard times. Quite the opposite, in fact. Margaret Thatcher is a case in point. When she assumed power in 1979, the country was in the grip of high unemployment, an ongoing recession and the fallout of widespread strikes by public sector trade unions in the Winter of Discontent.

“Things were not great,” Hurvenes says. “You could say the result was good or bad but she – maybe with quite harsh methods – whipped the country back into shape and turned it into the prosperous nation it has been ever since.”

Time to act

If the adage ‘Think crisis – think female’ is indeed true, then there has never been a better time for Britain to have a woman at the helm in the wake of the EU referendum.

If Merkel’s record is anything to go by, the odds are good. As the EU’s longest-serving and most powerful leader, she is no stranger to tackling problems, with Brexit and the refugee crisis the latest in a string of major issues to threaten the stability of the union.

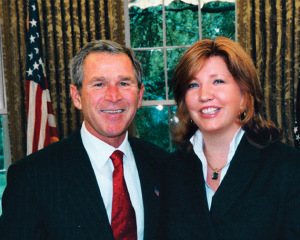

One by-product of women being elected into leadership roles at tough times is that they will be in the spotlight not just because they are female, as people instinctively look more to leaders during periods of uncertainty. While this might mean women in power are under even more pressure as a result, it is no bad thing that they are high profile and visible says Pippa Malmgren, former economic adviser to George W Bush and founder of London-based DRPM Group.

She says that while three women in charge might be an historic moment in itself, female leaders and influencers have been in charge of major issues for quite some time now and “nobody noticed”.

When The Economist published a list of the most influential economists in the world this year, measured according to the amount of media attention received, neither the IMF’s Lagarde nor the US Federal Reserve’s Janet Yellen and Esther George were featured in the top 15.

And while women rising to the top of their game in three of the biggest political arenas in the world is undoubtedly inspiring, Malmgren warns of an adverse consequence.

“There is a danger people will think that since we have loads of women in charge, there is no more issue,” she says. “But the fact is there are loads of issues, such as women not being paid as well as men, and women not being in non-executive director positions and senior management.”

The shortage of women in senior roles is widespread and the number of women in UK property – where representation hovers around 15%, as it has done for the last five years – still lags far behind where it should be. This despite evidence demonstrating the measurable business benefits of a diverse workforce (see below).

Could these figures – in property, politics and beyond – come down to the way that ambition manifests itself differently among men and women? Antonia Belcher, founding partner of surveyor Mellersh and Harding, believes so. As a transwoman with the experience of heading property businesses in both gender roles, she is perhaps one of the best-placed people in the industry to outline those distinctions.

“One fundamental difference between the girls and the blokes is that a lot of men have a massive hunger to get their boss’s job,” she says. “They do it ruthlessly and lie to the back teeth on their CVs. Women don’t play like that so it’s not a level playing field. They’re still trying to be polite, fair and equitable. But if they want gender equality, they have to try and work like that too.”

Malmgren suggests it comes down to the masculine and feminine qualities which, to varying degrees, both genders possess. What is crucial, she says, is having a full array of tools at your disposal. “There comes a moment when there’s a one-on-one fight, and one of you is going to lose,” she says. “If you want to play the game at the very top, there comes a point when feminine qualities don’t serve you well.”

So, when it comes to getting to the top spot, perhaps men have the ruthless edge. But does it really make a difference if a leader is a man or a woman? Thatcher, Merkel and Lagarde have all proven they are more than fit for some of the biggest jobs in the world. Grainger’s Helen Gordon, Vanessa Simms and Margaret Ford and a host of other female leaders have proven the same in property. And whether appointed at crisis points or not, they often outperform their male predecessors if financial achievements are anything to go by.

So when it comes to who runs the world, there are more women than ever making their mark, setting an example and inspiring future generations. Not because they are women. But because they are proving that a man is not always the best person for the job.

Women of the world

- In the top 20% of businesses by financial performance in 2014, 27% of leaders were women. In the bottom 20% of financial performers, only 19% of leaders were women. Source: DDI and The Conference Board

- The more women on a corporate board, the less a company pays for its acquisitions – by as much as 15.4% with each female director. Source: University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business

- Businesses with at least one female board member saw an average return on equity of 14.1% for the 10 years to 2015. By comparison, average returns for all-male boards were 11.2% in the same period. Source: Credit Suisse

• To send feedback, email janie.stamford@estatesgazette.com or tweet @JanieStamford or @estatesgazette